Sm-Co High-Temperature Permanent

Magnet Materials

Abstract

Permanent magnets capable of reliably

operating at high temperatures up to ~450°C are required in advanced power

systems for future aircraft, vehicles, and ships. Those operating temperatures are far beyond the

capability of Nd-Fe-B magnets. Possessing

high Curie temperature, Sm-Co based magnets are still very important because of

their high-temperature capability, excellent thermal stability, and better

corrosion resistance. The extensive

research performed around the year 2000 resulted in a new class of Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnets

capable of operating at high temperatures up to 550°C. This paper gives a detailed historical review

of the development of Sm-Co permanent magnets.

Phase diagram, crystal structures, and intrinsic magnetic properties of rare

earth-Co compounds are introduced. Emphasis is placed on Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets for operation at >300°C up to 550°C and thermal stability issues,

including instantaneous

temperature coefficients of magnetic properties. The significance of nanograin structure,

nanocrystalline and nanocomposite Sm-Co magnet materials, and prospects of

future rare earth permanent magnet materials are discussed.

Keywords: Sm-Co, Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17,

high-temperature magnets, nanocomposite

PACS: 75.50.Ww, 75.50.-y

1. Introduction

Applications of Nd-Fe-B magnets have rapidly expanded

since the mid-1980s. However, because of the low Curie temperature

of Nd2Fe14B compound (312ºC) and relatively low intrinsic

coercivity, high-end Nd-Fe-B magnets can be used only around room

temperature. Heavy rare earth, such as

Dy and Tb, modification enhances intrinsic coercivity to ~2.4 MA/m,

thus extending the operating temperature to ~180°C. Beyond that temperature, Nd-Fe-B magnets will

be no longer appropriate for any dynamic applications.

Permanent

magnet materials capable of reliably operating at high temperatures up to ~450°C

are required in the advanced power systems of future aircraft, vehicles, and

ships. A major objective of the advanced

power systems is to increase device reliability, maintainability, and

supportability. This advancement will be

accomplished in part through the development of advanced power components such

as magnetic bearings, integrated power units, and internal starter/generators

for main propulsion engines. New high

temperature magnets are enabling technologies for the development of these new

power components. Power system designers

frequently find that magnetic materials impose technological limitations on

their designs. Compromises are generally

required between the desired performance and the magnetic, mechanical, and

electrical properties of available materials.

If new materials can operate at >300°C, then new advanced designs will

be possible. Air

cooling, rather than complicated liquid cooling and its necessary

logistics support, will become an operational capability. Likewise, oil-less/lube-less gas turbine

engines and power systems will be possible [1].

Possessing high Curie temperatures

(727°C for SmCo5 and 920°C for Sm2Co17

compound), Sm-Co based magnets are still very important because of their

high-temperature application capability, excellent thermal stability, and

better corrosion resistance. The extensive

research performed around the year 2000 resulted in a new class of Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnets

capable of operating at high temperatures up to 550°C.

Another important trend in rare earth

permanent magnets research is nanocrystalline and hard/soft nanocomposite magnet

materials. For conventional rare earth

magnets, high uniaxial anisotropy is only a necessary condition for high

coercivity, but not necessarily a sufficient condition for it. Often, compositional modification and

specific heat treatment have to be imposed to develop useful coercivity, as in

the case of Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets. However, when the grain size is

reduced from micrometer to nanometer range, a direct connection between

magnetocrystalline anisotropy and intrinsic coercivity is established. This makes it possible to develop nanograin

Sm2(Co,Fe)17 and nanocomposite Sm2(Co,Fe)17/Fe-Co

magnets with significantly enhanced magnetization and Curie temperature, as a

result of eliminating excessive Sm and completely getting rid of non-ferromagnetic

Cu and Zr. The current

status of research in this field will be briefly introduced, and the technical

difficulties in making nanocomposite Sm-Co magnetic materials will be

discussed.

In this paper, a detailed historical

review of the development of Sm-Co permanent magnet materials is given and this

development is compared with that of Nd2Fe14B-based

magnets. Based on this comparison,

prospects of future rare earth permanent magnet materials are given.

2.

Historical Review of Development of Sm-Co Permanent Magnet Materials

Prior to the development of Sm-Co

permanent magnet materials the two important types of permanent magnets were

so-called Alnico magnets and hard-magnetic ferrites. Alnico was invented in the early 1930s in Japan.

It contained 24 wt% Co, 14% Ni, 8% Al, 3% Cu,

and 51% Fe (Alnico 5) and had a coercivity over 35 kA/m, or about double that

of the best magnet steels. Since then,

the properties of permanent magnets have rapidly improved. The maximum energy product of Alnico 5 reached

40 kJ/m3 in the 1940s and then 103 kJ/m3

in the modified Alnico in the 1960s. The

high coercivity in Alnico magnets was explained by shape anisotropy. The elongated strong ferromagnetic Fe-Co rich

phase is embedded in a weak magnetic Al-Ni rich matrix,

the shape anisotropy restricts the magnetization direction along the long axis

of the Fe-Co phase, making demagnetization difficult.

During the years from 1933 to 1945,

ferrites were developed into commercially useful

materials. Hard-magnetic ferrites have

the formula MO∙6Fe2O3 (where M=Ba

or Sr). They

have a hexagonal crystal structure and fairly large

magnetocrystalline anisotropy, resulting in high coercivity. Hard ferrites exhibit greater coercive force

(160-240 kA/m) but much lower remanence (0.25-0.35 T) and maximum energy

product (12-28 kJ/m3) than Alnico.

A major turning point for the

development of permanent magnets occurred in the 1960s. In the period 1946-1952, the study of rare

earth metals was greatly accelerated because of advances in chemical separation

techniques that were developed in association with the Manhattan Project,

1942-1945. Methods for producing pure rare

earth metals in quantity were developed which, in turn, stimulated interest in

the use of rare earth metals as alloying additions.

In 1959, Nesbit [2] presented

magnetic results for a series of Gd-Co alloys, which included the intermetallics GdCo2, GdCo3, and GdCo5,

and showed Gd and Co sublattices coupled antiparallel

in each of these phases. This was

followed in 1960 by the work of Hubbard [3] who observed for GdCo5 a

large coercive force of 637 kA/m, which he ascribed to a

large magnetocrystalline anisotropy.

The significance of this work was neglected, perhaps because Gd was

expensive and the magnetization of GdCo5 was rather low, and apparently it was not recognized that GdCo5 was

only one of a family of intermetallic compounds with potential for permanent

magnet applications.

In 1966, Hoffer

and Strant [4] reported that YCo5 had an extremely large crystal anisotropy with a single easy

axis of magnetization. The significance

of this discovery was immediately recognized, and they suggested that YCo5,

and most other RCo5 (R stands for rare earths) phases were potential

candidate materials for new permanent magnets.

Extensive studies followed to determine the permanent magnetic

properties of the family of RCo5 (1:5) compounds containing Y, Sm,

Ce, La, Nd, Pr, and mischmetal (MM) [5-17]. Out of these studies evolved a new generation

of permanent magnet materials with outstanding properties, which feature a

useful combination of high remanence and high coercivity.

Preliminary magnets made from YCo5

by Strnat’s group in 1966 had energy products of only

about 8 kJ/m3 [4] and in 1967 the same group reported an energy

product of 40.6 kJ/m3 for SmCo5 [5]. Further improvements in energy product to 64.5

kJ/m3 and then 147.2 kJ/m3 were reported in 1968 by Velge and Buschow [10,12] at Philips. The

development of liquid-phase sintering techniques by Das

[14] in 1969 and by Benz and Martin [16] in 1970 made fully dense and stable

SmCo5 magnets possible. The

energy products reached by the latter methods ranged from 127 to 159 kJ/m3

and culminated in the basic manufacturing technology for the “first generation”

of commercial rare earth permanent magnets (REPM). Today, the best (BH)max

of SmCo5 is around 200 kJ/m3. Partial substitution of Pr for Sm resulted in

slightly enhanced magnetization and energy product.

The promise which the rare

earth-cobalt intermetallic phases R2Co17 (2:17) held as potential permanent magnets

was recognized in the early 1970s. Basic

properties such as saturation magnetization, Curie temperature, and

crystallographic parameters of the binary compounds were studied in the

mid-1960s at the US Air Force Materials Laboratory by Strnat’s

group [18]. From 1970-1973, Ray, Strant, Mildrum, and their

co-workers [19-25] at the University of Dayton expanded the study to the

quasi-binary R2(Co1-xFex)17 phases

and systematically investigated the metallurgical and magnetic properties,

including the magnetocrystalline anisotropy of these phases. The fact that 2:17 compounds, with or without Fe

substitution, have substantially greater saturation magnetization values (1.2-1.6

T) led them to predict that a “second generation” of rare earth magnets with

higher energy product was possible [19-24].

However, the realization of practical

2:17 magnets proved more difficult. It was found that all the magnet fabrication

methods that had worked well for SmCo5, when applied to Sm2Co17,

yielded only very low coercive force, usually less than 0.2 MA/m. Over a period of several years, many

different experimental approaches were tried but no exciting results were

obtained.

In 1974, Senno

and Tawara [26] extended the range of Sm(Co,Fe)z

to z = 7.2 by adding Cu, so that the alloys could be magnetically precipitation

hardened. They obtained two-phase

sintered magnets in which the main phase has the 2:17 structure. Careful heat treatment made the coercivity in

the 0.32-0.8 MA/m range. Later Tawara and Senno [27] were able

to obtain high coercivity in sintered Sm(Co0.85Fe0.5Cu0.10)8. In 1976 Nagel [28] achieved energy products

in excess of those for SmCo5 in sintered magnets Sm(Co,Fe,Mn,Cr)8.5.

However, the Mn- and Cr-containing magnets had the severe disadvantage that

its coercive force drops very quickly with increasing temperature above 20ºC.

An important breakthrough was made in

1977 when a group at TDK in Japan announced that the Fe content could

be increased and the Co content lowered if these compositional change were

accompanied by a small addition of Zr or similar transition metals [29,30]. They obtained Br=1.12

T, MHc =0.6 MA/m, and (BH)max

= 240.3 kJ/m3 for an alloy corresponding to the nominal composition

Sm(Co0.674Fe0.213Cu0.100Zr0.013)7.43. Further refinement of the isothermal aging

and step aging heat treatment [31] and compositional adjustment [32] yielded a permanent

magnet with Br=1.2 T, MHc =1 MA/m, and (BH)max = 262.6 kJ/m3 for the nominal

composition Sm(Co0.65Fe0.28Cu0.05Zr0.02)7.67. It is important to note that these magnets

have a much better temperature coefficient of MHc

than the Mn-and Cr-containing magnets, making them much more useful for

elevated-temperature applications. The 2:17 magnets, or the “second generation”

rare earth permanent magnets, became commercially available in the early

1980s. The best magnetic properties of (BH)max

= 271 kJ/m3, Br = 1.22 T, MHc = 1.35

MA/m were obtained in Sm(Co0.613Fe0.316Cu0.052Zr0.019)7.88,

a magnet containing low Sm, low Cu, and low Zr, but fairly high Fe [33].

3.

Phase Diagram and Crystal Structures

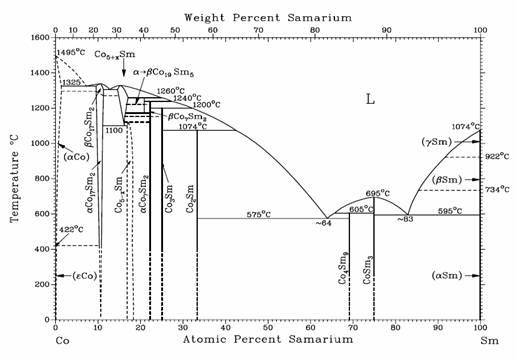

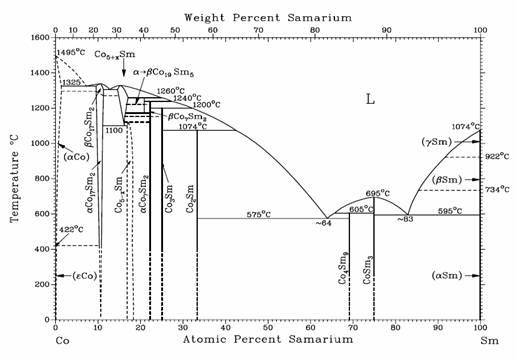

Figure 1 shows the binary Sm-Co phase

diagram [34-36]. There exist quite a few

intermetallic compounds in the Sm-Co system, including Sm2Co17,

SmCo5, Sm2Co7, SmCo3, SmCo2,

Sm9Co4, and Sm3Co. Among them, SmCo5 and Sm2Co17

possess important technical significance.

Sm2Co17 is the most Co-rich compound, and it has a

polymorphic phase transformation (aCo17Sm2 and bCo17Sm2

in Figure 1) and has different crystal structures at high and low temperatures. In addition, Sm2Co17 and

SmCo5 demonstrate finite homogeneity ranges, while others show as

line compounds. The R-Co phase diagrams

for other rare earths are generally similar, but with some minor systematic

variations.

As shown in Figure

2 [37], SmCo5 has a hexagonal

crystal structure (1:5H, space group: P6/mmm;

prototype: CaCu5), while Sm2Co17 has a rhombohedral crystal structure (2:17R, space

group: Rm; prototype: Th2Zn17)

at room temperature and a hexagonal crystal

structure (2:17H, space group: P63/mmc;

prototype: Th2Ni17) at high temperatures (1300-1340ºC). The common characteristic of all these three

crystal structures is that their c-axes are the unique easy magnetization

directions. This uniaxial anisotropy is

the basis for SmCo5 and Sm2Co17 to become

high-performance permanent magnets.

Fig. 1. Binary Co-Sm

equilibrium phase diagram.

(a) 1:5 H (b) 2:17 R (c) 2:17 H

Fig. 2. Crystal structures of SmCo5

(1:5 H) (a); Sm2Co17 (2:17 R) (b); and Sm2Co17

(2:17 H) (c).

4.

Intrinsic Magnetic Properties of R-Co compounds

Three important prerequisites for

high-performance permanent magnet materials are high saturation magnetization,

high Curie temperature, and high uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Saturation magnetization and Curie

temperature values of the R-Co binary systems are illustrated in Figures 3 and

4, respectively. As a

general rule for the 4f-3d exchange interaction, the light rare earths

couple parallel with Co, yielding high saturation magnetization, while the

heavy rare earths couple antiparallel with Co, resulting in low saturation

magnetization.

Fig. 3.

Room-temperature saturation magnetization values of RCo5 and R2Co17

compounds.

Fig. 4. Curie temperatures of RCo5

and R2Co17 compounds.

Figure 5 shows anisotropy field, Ha, for binary RCo5

compounds with R = Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, and MM. It is obvious that SmCo5 compound

has the highest anisotropy field. Figure

6 shows anisotropy field, Ha, for binary R2Co17

compounds with R = Y, Ce, Pr, Nd, and Sm.

It is obvious that for all 2:17 compounds,

only Sm2Co17 has uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy

and possesses a moderately large crystalline anisotropy field.

Fig. 5. Anisotropy field, Ha,

for binary RCo5 compounds.

Fig. 6. Anisotropy field, Ha,

for binary R2Co17 compounds.

It is well known

that for a rare earth-transition metal (RE-TM) compound, Curie temperature is

primarily determined by the TM sublattice, while crystalline

anisotropy is primarily contributed by the RE sublattice

unless at temperatures close to the Curie point. Research on RE-TM compounds indicates that

among all 3d transition metals, Co provides the highest Curie temperature,

while among all light rare earths, Sm usually provides the highest crystalline

anisotropy. One exception is the cubic

Laves 1:2 compounds for which the Fe compounds have higher Curie temperature

than the Co compounds.

Figure 7 shows

Curie temperature, TC, versus Co content for Sm-Co binary compounds.

In this figure, Curie temperature data

for LaCo13 and Sm2Co14B are also included. It can be seen from Figure 7 that there exists

a linear relationship between Curie temperatures and the Co content, which

clearly demonstrates the importance of the Co content to Curie temperature. Similarly, there exists a linear relationship

between saturation magnetization and the Co content, as shown in Figure 8.

Fig. 7. Curie temperature, TC,

versus Co content for Sm-Co binary compounds. Data for LaCo13 and Sm2Co14B

are also included.

Fig. 8. Saturation

magnetization versus Co content for Sm-Co binary compounds. Date for LaCo13

is also included.

Table 1 lists

intrinsic properties of some R-Co

compounds. It

is shown that of

all light rare earth-Co compounds, SmCo5 possesses the

highest magnetocrystalline anisotropy, while Sm2Co17 combines

high saturation magnetization, high Curie temperature, and moderately

high anisotropy. As for heavy rare

earth-Co compounds, HRCo5 and HR2Co17 (with HR = Gd, Tb, and Dy) have

low saturation magnetization, while Tm2Co17

Yb2Co17, and Lu2Co17

have fairly high

saturation magnetization, but with unfavorable magnetocrystalline anisotropy,

except for Tm2Co17, which shows uniaxial anisotropy, but

its anisotropy field is not high. A small

amount of Fe substitution for Co in Tm2Co17 slightly

increases its anisotropy field. For Yb2Co17

and Lu2Co17,

a small amount of Fe substitution for Co changes the anisotropy from easy-basal-plane to uniaxial, though the anisotropy fields are

not high in both cases.

5.

Sm-Co Permanent Magnets capable of operating up to 300ºC

Sm-Co permanent magnets are based on

SmCo5 and Sm2Co17 compounds. The composition of a SmCo5 magnet

is slightly Sm rich, as compared with its chemical stoichiometry. Its microstructure is

basically a featureless single phase, while a small amount of oxide

particles and sometimes a minor Sm2Co7 phase can also

exist. It is a generally accepted idea

that the coercivity of SmCo5 magnet is determined by nucleation

field, though it is believed that grain boundary pinning may also play an

important role.

On the other hand, the composition

and microstructure of Sm2Co17-based magnets are more complicated. As mentioned in Section 2, in order to

develop useful coercivity, extra Sm is required and considerable amount of Cu

and Zr has to be added into the alloy.

In addition, a complex and long-term heat treatment procedure must be

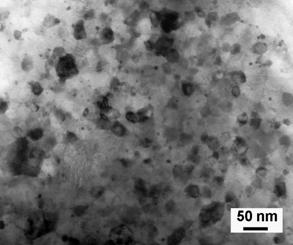

employed (the detailed heat treatment procedure is given in Section 8). Figure 9 shows a TEM

microstructure of a typical Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnet

[40]. Sintered

2:17 magnets have grains of micrometers

in size, with a

fine, nanometer cellular structure

within each grain. As shown in Figure 9,

the cellular structure consists of three

coherent phases: a 2:17 cell interior phase; a 1:5 cell boundary

phase rich in Sm and Cu; and a platelet phase rich in Zr. It is believed that the domain wall pinning

in the 1:5 cell boundary phase is the origin of high coercivity.

Table 1. Intrinsic

properties of some R-Co compounds at room temperature.

|

Compound

|

m0Ms (T)

|

TC

(K)

|

K1

(MJ/m3)

|

Ha (MA/m)

|

Anisotropy type

|

References

|

|

YCo5

|

1.06

|

987

|

6.5

|

10.3

|

uniaxial

|

[37,38]

|

|

LaCo5

|

0.91

|

840

|

6.3

|

13.9

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

CeCo5

|

0.77

|

653

|

6.4

|

16.7

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

PrCo5

|

1.20

|

893

|

8.1

|

13.5

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

NdCo5

|

1.23

|

910

|

0.7

|

0.4

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,38]

|

|

SmCo5

|

1.07

|

1020

|

17.2

|

~35

|

uniaxial

|

[37,38,39]

|

|

GdCo5

|

0.18

|

1008

|

4.6

|

~21

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

TbCo5

|

0.24

|

973

|

|

0.5

|

easy basal plane

|

[37]

|

|

DyCo5

|

0.30

|

966

|

|

2.0

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

HoCo5

|

0.53

|

992

|

|

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

ErCo5

|

0.64

|

978

|

4.5

|

8.0

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

TmCo5

|

0.67

|

1012

|

|

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

Y2Co17

|

1.25

|

1167

|

-0.34

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,38]

|

|

Ce2Co17

|

1.15

|

1053

|

|

1.2

|

easy basal plane

|

[37]

|

|

Pr2Co17

|

1.38

|

1153

|

-0.6

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37]

|

|

Nd2Co17

|

1.39

|

1150

|

-1.1

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,38]

|

|

Sm2Co17

|

1.22

|

1190

|

3.3

|

5.4

|

uniaxial

|

[37,38,39]

|

|

Sm2(Co0.7Fe0.3)17

|

1.45

|

1113

|

3.0

|

4.1

|

uniaxial

|

[37]

|

|

Gd2Co17

|

0.75

|

1193

|

-0.5

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37]

|

|

Tb2Co17

|

0.66

|

1188

|

-3.2

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,90]

|

|

Dy2Co17

|

0.68

|

1152

|

-2.6

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,38]

|

|

Ho2Co17

|

0.84

|

1155

|

-0.9

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,90]

|

|

Er2Co17

|

0.91

|

1186

|

0.72

|

2.5

|

uniaxial

|

[37,38,92]

|

|

Tm2Co17

|

1.21

|

1180

|

0.56

|

2.6

|

uniaxial

|

[37,91]

|

|

Tm2(Co0.82Fe0.18)17

|

1.42

|

1153

|

|

3.0

|

uniaxial

|

[41,42,91]

|

|

Yb2Co17

|

1.36

|

|

|

|

easy basal plane

|

[37]

|

|

Lu2Co17

|

1.40

|

1203

|

|

0.9

|

easy basal plane

|

[37,91]

|

|

Lu2(Co0.85Fe0.15)17

|

|

|

|

2.1

|

uniaxial

|

[91]

|

(a) (b)

Fig. 9.

TEM micrographs of a sintered Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnet. (a) Section perpendicular

to the alignment direction; (b) Section parallel to the alignment

direction.

Arrow (→) on (b) is the alignment direction (c- axis) [40].

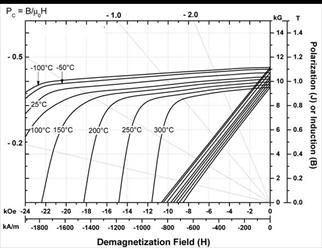

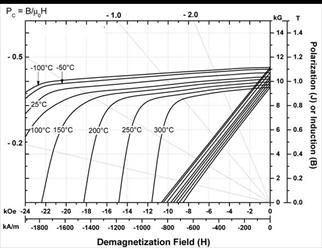

Demagnetization curves of commercial

SmCo5 and Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnets at

various temperatures are shown in Figures 10 and 11 (By courtesy of Electron

Energy Corporation).

Both types of magnets can be used up to 300ºC.

Fig. 10. Demagnetization curves of commercial SmCo5

magnets.

Fig. 11. Demagnetization curves of commercial Sm2TM17

magnets.

Permanent magnets with very low temperature coefficients of

magnetization over a wide temperature range are required for many

applications. Examples are microwave

tubes, gyros, accelerometers, and conventional moving-coil meters. The flux provided by most permanent magnets

decreases on heating. This is an intrinsic

property for all ferromagnetic materials, in which the magnetization will

eventually drop to zero at their Curie temperatures. On the other hand, for most heavy rare

earth-Co compounds, for example GdCo5 and Gd2Co17,

the magnetization increases when temperature enhances before reaching a peak

value. Based on this characteristic,

partial substitution of heavy rare earth, such as Gd, for Sm can be made to

form temperature-compensated (Sm,Gd)-Co magnets which

may show a near zero temperature coefficient

of magnetization from -50°C to about 150°C with a peak magnetization at around

room temperature. Demagnetization curves

of commercial temperature-compensated (Sm,Gd)Co5 and (Sm,Gd)2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets at various temperatures are shown in Figures 12 and 13 (By courtesy of

Electron Energy Corporation). Both types of temperature-compensated magnets

can be used up to 300ºC.

It is obvious from Figure 3 that Tm2Co17,

Yb2Co17, and Lu2Co17 have much

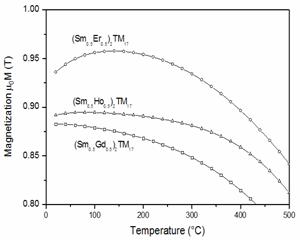

higher magnetization than Gd2Co17. Figure 14 compares temperature dependences of

magnetization for Sm2TM17 and Tm2(Co,Fe)17. If Tm, Yb, or Lu can be incorporated into

temperature-compensated (Sm,Gd)-Co magnets, then improved magnetic performance

could be expected. However, because R2Co17

(R = Tm, Yb, Lu) have poor anisotropy, developing enough high coercivity would

be a technical challenge.

Powder metallurgy is used to

manufacture commercial Sm-Co magnets.

Its processing procedures include vacuum melting, ingot crushing, ball

or jet milling, powder magnetic alignment, compaction, sintering and heat

treatment. Alternatively, Sm-Co alloy

powders can be produced by a reduction-diffusion process using Sm2O3,

Co powder, and Ca or CaH2 as a reduction agent.

Sintered Sm-Co magnets are very hard

and brittle, therefore machining them into the

final shape and size is often troublesome, especially for tiny magnetic

parts. This led to the development of

bonded Sm-Co magnets [37], which are made by consolidating a magnet powder with

a polymer matrix. Thermosetting binders,

such as epoxy resin, are employed for use in compression-molded magnets, while thermoplastic binders, like nylon, for

injection-molded magnets, and elastomers, such as rubber, are used for extruded

magnets [43]. Table 2 lists magnetic

properties of some Sm-Co magnets.

Fig. 12. Demagnetization curves of (Sm,Gd)Co5

magnets.

Fig. 13. Demagnetization curves of (Sm,Gd)2TM17-type

magnets.

Fig. 14. Saturation magnetization vs. temperature for

Tm2(Co0.82Fe0.18)17, Tm2(Co0.94Fe0.06)17

[41,42], and a Sm(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)~7.

Table 2. Magnetic

properties of some commercial Sm-Co magnets (TM stands for Co,Fe,Cu,Zr).

|

Magnets

|

m0Mr (T)

|

MHc (kA/m)

|

BHc (kA/m)

|

(BH)max (kJ/m3)

|

|

SmCo5, (Sm,Pr)Co5

|

0.8-0.96

|

>1,900

|

635-740

|

135-190

|

|

Sm2TM17

|

1.0-1.2

|

>1,900

|

710-840

|

180-255

|

|

Temp. compensated (Sm,Gd)Co5

|

0.5-0.75

|

>1,900

|

400-600

|

64-120

|

|

Temp. compensated (Sm,Gd)2TM17

|

0.8-0.95

|

>1,900

|

480-720

|

80-175

|

|

Bonded SmCo5

|

0.4-0.5

|

600-1,600

|

240-520

|

32-65

|

|

Bonded Sm2TM17

|

0.6-0.8

|

400-1,600

|

310-520

|

64-130

|

6.

High-Temperature Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type Magnets Capable

of Operating up to 550°C

Possessing

the highest Curie temperature and moderately high magnetization and energy

product among high-performance rare earth permanent magnets, Sm2TM17

magnets are the best conventional high-temperature permanent magnets [44,45]. A conventional Sm2TM17

magnet can operate at up to 300°C. The problem associated with higher

temperature (> 300°C) operation was that the intrinsic coercivity (MHc) of these magnets drops sharply

with increasing temperature. Upon

heating, MHc of the 2:17 magnets drops sharply from their

room temperature values of 1.5-2.5 MA/m (or higher) to only 0.2-0.5 MA/m at

400°C and 0.1-0.2 MA/m at 500°C. Low

intrinsic coercivity at high temperatures results in a nonlinear 2nd

quadrant induction demagnetization curve (B curve) above ~300ºC. A linear 2nd

quadrant B curve is critical for all dynamic applications, such as for

generators, motors, and actuators.

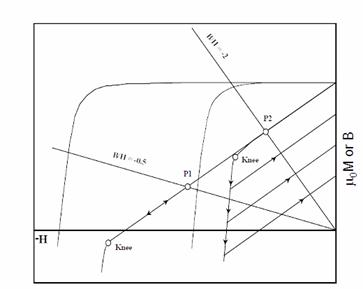

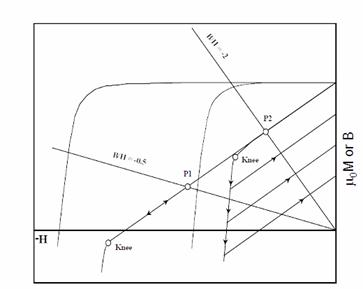

In a dynamic

application, the operating point of a magnet keeps cycling on the B curve. If the intrinsic coercivity is low, then the B

curve can be nonlinear and a knee appears.

Under this circumstance, the operating point of the magnet can be

reduced to below the knee in the B curve and the induction can be significantly

reduced irreversibly. If the intrinsic

coercivity of a magnet is sufficiently high, then the B curve will be linear

and the induction will be reversible around the operating point even at a quite

low permeance value as shown in Figure 15.

The maximum operating temperature of a magnet (Tmax) can be

defined as the temperature limit at which the B curve of the magnet still maintains

linearity. Therefore, to increase the

operating temperature of permanent magnet materials, the key is to increase

their intrinsic coercivity at high temperatures, so that their induction

demagnetization curves remain linear at the operating temperature.

Fig. 15. Intrinsic

coercivity and linearity of an induction demagnetization curve.

Around

the year 2000, extensive research was carried out to substantially improve the

high-temperature performance of Sm2TM17-type

permanent magnets. As a result of that effort,

the maximum operating temperature of permanent magnets was increased from

around 300°C to as high as 550°C. This advance

was made on systematic studies of the effects of compositions on high-temperature

intrinsic coercivity of Sm2TM17-type of permanent

magnets.

6.1 Effects of

compositions on high-temperature intrinsic coercivity of Sm-TM permanent

magnets

Compositions

play a critical role in determining coercivity of Sm2TM17-type

magnets. It is important to realize,

however, that (1) the effect of an element on coercivity may be different at

room temperature from what it is at elevated temperatures - this is especially

true for Fe and Sm; (2) the enhancement of an element on coercivity may have a

peak value, and the optimal content corresponding to the peak coercivity value is

often different at different temperatures; (3) there exist interactions among

different alloy components. All these

factors make the effects of compositions on coercivity very complicated.

Fe is

an important element for substituting Co in binary R2Co17

compounds. Fe substitution for Co always

enhances magnetization, but decreases Curie temperature. The effect of Fe substitution on crystalline

anisotropy of R2Co17 is usually favorable at least around

room temperature. R2Co17

(R = Ce, Pr, Gd, Yb, Lu, and Y) demonstrate unfavorable easy-basal-plane

anisotropy. However, substitution of an

appropriate amount of Fe for Co changes the anisotropy to uniaxial. On the other hand, R2Co17

(R = Sm, Er, Tm) demonstrate uniaxial anisotropy and this anisotropy remains up

to around 50 at% - 60 at% Fe substitution.

Increasing

Fe content in Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnets effectively

enhances magnetization and leads to higher energy product. It also increases the room temperature

intrinsic coercivity before a peak value is reached. However, high Fe content results in

significantly low coercivity at elevated temperatures, especially at temperatures

above 400°C. Therefore, in order to obtain high coercivity

at high temperatures, the Fe content in conventional Sm2TM17-type

magnets has to be decreased. A high

intrinsic coercivity of 0.66 MA/m at 400°C was achieved when the Fe content was

decreased from 15 - 20 wt% in conventional Sm2TM17 to 7

wt%.

Sm also strongly

affects intrinsic coercivity at both room temperature and elevated

temperatures. The intrinsic coercivity

is very sensitive to the Sm content around room temperature. Generally speaking, increasing Sm content

results in much lower room temperature coercivity but higher coercivity at high

temperatures. With increasing the Sm

content, the sensitivity of coercivity to Sm content is

gradually reduced and the coercivity peak tends to shift to the higher

Sm content direction.

When dealing with the effect of Sm content (or z value) in

Sm(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)z magnets, it is important to realize that a small

amount of Sm exists in the form of Sm2O3. Because Sm is a very active element, and some

Sm is oxidized during the fine-powder processing. Under normal conditions, a sintered Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnet contains 0.3 - 0.6 wt% oxygen. It

is easy to understand that oxygen reduces the effective Sm content by 6.27

times the weight fraction of the oxygen. This means that for each 0.1 wt% oxygen there

will be 0.627 wt% Sm to be consumed and reacted with oxygen. For this reason, every effort should be made

to reduce oxygen pickup during processing.

It is well known

that coercivity in the Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets originates from the pinning of domain walls in the Cu-rich cell

boundary phase in the fine-scaled cellular microstructure [32,46]. Therefore, sufficient Cu content is essential

to develop high coercivity at both room temperature and high temperatures. Generally speaking, MHc

increases with the Cu content monotonously and

increasing Cu content leads to higher coercivity at all temperatures.

Zr has an

important effect on coercivity in the Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets. It has been observed that Zr is

critical in developing high coercivity at both low and high temperatures,

especially for magnets containing a relatively higher Fe content. It was observed that intrinsic coercivity

rapidly increased with increasing Zr and a peak coercivity value was reached at

an optimum Zr content. The squareness of

the 2nd-quadrant demagnetization curve is strongly dependent on the

Zr content in magnet alloys. The knee

field (the demagnetizing field corresponding to 0.9Br) is rapidly

enhanced with increasing Zr content. The

effects of other transition metals, such as Ti, Hf, Nb, V, Ta, Cr, and Ni, on

the high-temperature coercivity of Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17

were also investigated. All those elements

decreased magnetization and only Nb demonstrated an effect of slightly

enhancing coercivity at high temperatures.

6.2

New high-temperature Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnets

Based on

systematic studies of the effects of compositions on high-temperature

properties of Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type magnets, a new

series of sintered permanent magnets with significantly improved

high-temperature performance were accomplished by significantly reducing the Fe

content, increasing the Sm content, and adjusting the Cu and Zr contents in

magnet alloys. The maximum operating

temperature of these magnets was increased from previous 300°C for conventional

high-temperature magnets to as high as 550°C. The MHc of these new

magnets reached 1 MA/m at 400°C (two to three times higher than conventional magnets)

and 0.72 MA/m at 500°C (four to nine times higher than conventional magnets). The B curves of these new magnets remain

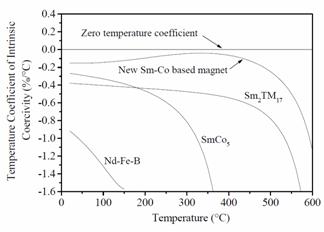

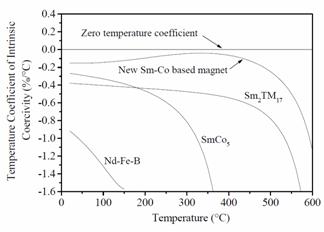

linear up to 550°C (250 to 350°C higher than conventional magnets). The temperature coefficients of MHc

for the new magnets can range from a small negative value (-0.03%/°C), to near

zero, or they may even be positive (up to +0.3%/°C). As a comparison, the temperature coefficients

of MHc for conventional SmCo5, Sm2TM17,

and Nd2Fe14B-based magnets around room temperature are

-0.3%/°C, -0.3%/°C, and -0.9 %/°C, respectively.

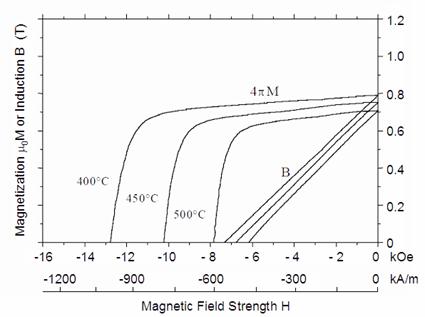

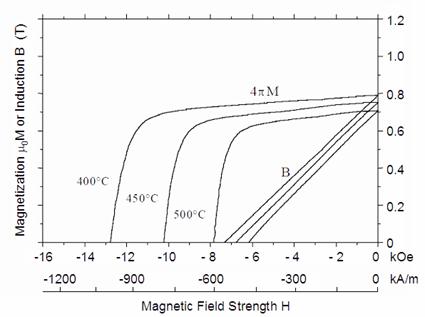

Figure 16 shows

demagnetization curves of a Sm(Co0.79Fe0.09Cu0.09Zr0.03)7.69

at 400, 450, and 500°C, respectively [47]. This magnet demonstrates much higher MHc

and better squareness of demagnetization curves at high temperatures than the

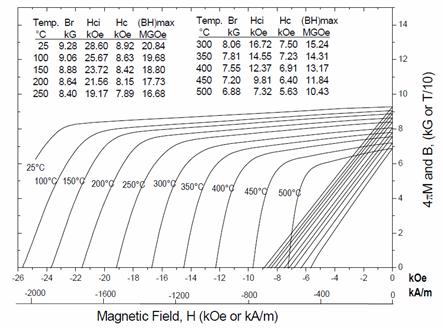

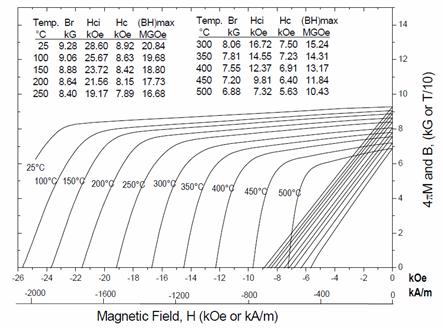

conventional 2:17 magnets. Figure 17 shows

demagnetization curves of a commercial new high-temperature magnet with its

maximum operating temperature Tmax = 500°C [48]. It can be seen from the figure that the room

temperature (BH)max of the magnet with Tmax = 500 is

around 166 kJ/m3. As a result

of excessive amount of Sm, Cu, and Zr, the magnetization values of these new

magnets are relatively low.

Figure 18 is a

TEM micrograph of a new high-temperature magnet with Tmax = 500°C. Comparing with that of the conventional 2:17 magnet (Figure 9), the cellular structure has smaller cells and

thicker cell boundaries.

Fig. 16. Demagnetization

curves of Sm(Co0.79Fe0.09Cu0.09Zr0.03)7.69

at 400°C, 450°C, and 500°C.

6.3 Long-term thermal stability of

new high-temperature permanent magnets

Figure 19 gives flux density loss versus time for a

new magnet with Tmax = 500°C

and conventional 2:17 magnets with (BH)max = 223

and 234 kJ/m3 (28 and 30 MGOe) during long-term aging at 500°C in

air. It can be seen from the figure that

after aging for 2,000 hours, the flux density loss was around 18%, 49%, and

69%, respectively [49]. The improvement

of the new magnet is obvious.

The flux density loss is caused by three different

mechanisms: (1) non-linear induction demagnetization curve (B curve); (2)

oxidation starting from the surface and gradually penetrating to the magnet

interior; (3) microstructure change, such as grain growth and phase

transformation. The flux density loss

caused by microstructure change is very limited, especially when the operating

temperature is lower than 400°C. When a magnet is operating at a temperature

higher than its TM, its non-linear B curve will result in a large

irreversible flux density loss. This is

the case for conventional 2:17 magnets

shown in Figure 19. On the other hand,

the loss for the new magnet is caused primarily by the

oxidation. Surface coating using Cr, W or sulfamate Ni can significantly reduce the flux

density loss caused by oxidation [50]. In

addition, it was determined that Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets demonstrated much better neutron radiation resistance as compared to

Nd-Fe-B type magnets. It was noted that the radiation resistance and thermal stability

are somewhat related and the irradiation damage is most likely caused by a

radiation-induced thermal effect. The excellent

radiation resistance of 2:17 magnets proved to be an advantage in space applications

[51].

Fig.

17. Demagnetization curves of a new

high-temperature magnet with Tmax = 500°C.

Fig. 18. TEM micrograph of a new high-temperature

magnet with Tmax = 500°C. 1 -

Cell; 2 - Cell boundary; 3 - Platelet. (By J. Fidler of the University of Vienna, Austria.)

Fig. 19. Long-term thermal stability of a new-high

temperature magnet with Tmax = 500°C.

6.4 Abnormal temperature dependence of intrinsic coercivity

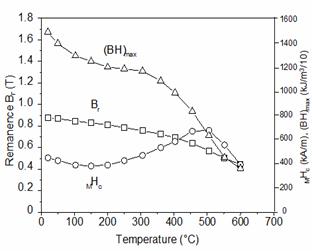

Novel temperature

dependence of MHc was observed during the research on high-temperature

permanent magnets in some newly-developed magnets. A positive temperature coefficient of

intrinsic coercivity in SmTMz with z = 7

was reported in 1998 [52]. In 1999, a

complex temperature coefficient in Sm(Co0.843Fe0.04Cu0.09Zr0.027)7.26

that had a low Fe content and a high Cu content was observed [47]. When heating this magnet, MHc

first gradually decreases and reaches a minimum at about 150°C as shown in

Figure 20. With continued heating, the MHc

rapidly increases and forms a maximum at 500°C. The MHc value of this

magnet at 500°C is more than 30% higher than its room temperature value. Another magnet of Sm(Co0.825Fe0.1Cu0.05Zr0.025)7.38

that has low Cu content displays a maximum MHc at 550°C,

which is nearly four times higher than its room temperature coercivity value as

shown in Figure 21. The

abnormal temperature dependence of coercivity in 2:17 magnets was observed by Russian

researchers as early as in 1990

[53].

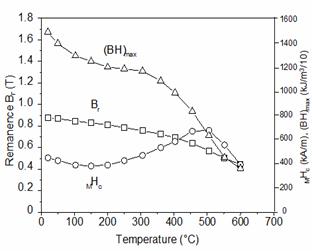

Fig.

20. Temperature dependence of magnetic

properties of Sm(Co0.843Fe0.04Cu0.09Zr0.027)7.26.

Fig.

21. Abnormal temperature dependence of

coercivity for Sm(Co0.825Fe0.1Cu0.05Zr0.025)7.38.

7.

Thermal stability, Temperature Coefficient, and Modeling of Temperature-

Compensated Magnets

7.1 Reversible and irreversible flux density

loss

The

open-circuit magnetic flux density loss caused by heating can be divided into

two categories:

- Reversible loss. It can be recovered when the temperature

returns to its original point.

- Irreversible loss.

- Type I irreversible loss. It cannot be recovered

even when the temperature returns to its original point, but can be

recovered by re-magnetizing.

- Type II irreversible loss. It cannot be recovered even by

re-magnetizing.

Normally, intrinsic coercivity decreases with increasing

temperature. If a magnet remains its

linear induction demagnetization curve at an elevated temperature, the

open-circuit magnetic flux density loss is reversible. However, if at an elevated temperature, a

knee appears on the induction demagnetization curve and the operating point of

the magnet is close to the knee, then the magnetic flux density loss cannot be

completely restored when the temperature returns to its original point, but the

loss can be recovered by re-magnetizing.

The type II irreversible loss cannot be restored even by re-magnetizing,

because this type of loss is caused by microstructural changes, such as grain

growth, phase transformation, and oxidation at elevated temperatures as

mentioned previously.

It is

obvious that approaches to improving the thermal stability of a magnet include

(1) effectively increasing its intrinsic coercivity so that its induction

demagnetization curve keeps linear at the operating temperature and, (2)

protecting the magnet from oxidation and any structural changes.

7.2 Temperature coefficient

To describe the temperature

dependence of a magnetic quantity, the temperature coefficient is often used

and it is defined as follows.

a(T1→T2) =  x 100 [%/ºC]. (1)

x 100 [%/ºC]. (1)

where a(T1→T2) is the temperature coefficient of Q over the temperature interval

from T1 to T2.

However, a(T1→T2) is an average of temperature coefficients of Q over the temperature

interval T1→T2, it is not necessarily an accurate description of the

temperature dependence of Q, especially when the interval between T1and T2,

is large. Further, when Q is not a monotonous function of temperature T, equation (1) may give a misleading result.

On

the other hand, the temperature coefficient of Q at a specific temperature T can be defined as

a(DT→0) =  x 100 [%/ºC]. (2)

x 100 [%/ºC]. (2)

When DT approaches 0, equation (2) leads to

aT =  x 100 [%/ºC]. (3)

x 100 [%/ºC]. (3)

Obviously,

aT gives the temperature coefficient of Q

at a specific temperature T. It is the "true" (or instantaneous) temperature coefficient and is a more

accurate description of the temperature dependence of Q. Unfortunately, in practice, it is

impossible to calculate aT when DT=0 by simply using (2). This problem can be readily resolved if we

use a polynomial to represent Q.

Q(T) = a0 + a1T +

a2T2 + … + anTn =  (4)

(4)

Coefficients

a0, a1, a2

and an in (4) can be

determined using a least square fit, and it is very easy to determine the

derivative of a polynomial. Therefore,

we have

= a1 + 2a2T + … + nanTn-1

=

= a1 + 2a2T + … + nanTn-1

=  (5)

(5)

Substituting

(4) and (5) in equation (3), yields

aT =  x 100 [%/ºC] (6)

x 100 [%/ºC] (6)

Using

(6), the

"true" temperature coefficients aT of any magnetic

parameter Q at any temperature T can be readily determined and a plot of temperature coefficient

versus temperature (aT vs. T) can

be drawn. Normally, since aT is more sensitive to T than Q, the aT vs. T plot is a very useful tool to represent temperature

characteristics of a magnetic parameter.

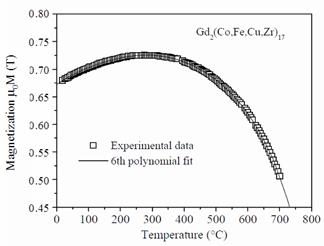

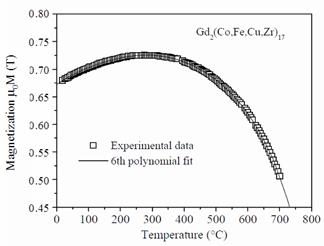

As an example,

Figure 22 shows the temperature dependence of magnetization at 0.8 MA/m for a

sintered Gd2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17 magnet. In the figure, the squares represent

experimental data, while the curve is a 6th degree polynomial

fit. In any experimental

characterization, random errors are always associated with the results of

measurements. The least square fit

eliminates those random errors and, therefore, the numerical result is

generally a better representation in comparison to the original experimental

data. Figures 23 through 25 are plots of

temperature coefficients of magnetization, intrinsic coercivity, and maximum

energy product versus temperature for some sintered rare earth permanent

magnets. This concept can be further

developed for modeling of temperature coefficients of magnetization for

temperature-compensated rare earth permanent magnets.

Fig.

22. Temperature dependence of

magnetization at 0.8 MA/m of Gd2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17.

Fig.

23. Temperature coefficients of

magnetization at 0.8 MA/m for some rare earth permanent magnets.

7.3 Modeling of temperature-compensated magnets

In addition to

Gd, other heavy rare earths, such as Er and Ho can also be used to make

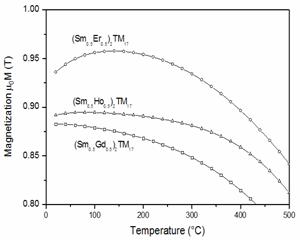

temperature-compensated magnets. Figure

26 compares temperature dependence of magnetization for a few heavy rare earth

2:17-type compounds. It can be seen from

the figure that Er2TM17 has the highest magnetization,

while Ho2TM17 has the highest Tp (temperature

corresponding to the peak magnetization).

Experiments indicated that Gd2TM17 has high

coercivity, while both Er2TM17 and Ho2TM17

showed low coercivity. Thus, it would be

difficult to make a good temperature compensated magnet by using only one

single heavy rare earth. To obtain a

temperature-compensated permanent magnet with a high coercivity, a high

magnetization, a high temperature for the peak magnetization, and a large

temperature range for compensation, it seems Gd, Er, Ho, and probably more

heavy rare earths, such as Tm, Yb, and Lu as previously mentioned, would have

to be used. This typically requires

considerable laboratory effort to determine the optimum combination of the

light rare earth and the heavy rare earths.

In research practice, a method of blending powders is often used. For example, by melting only two alloys of

SmCo5 and GdCo5, any magnet alloys that have the

composition of (Sm1-xGdx)Co5, with 0 £

x £ 1 can be obtained by blending powders of SmCo5 and

GdCo5.

Fig.

24. Temperature coefficient of intrinsic

coercivity for some rare earth permanent magnets.

Fig.

25. Temperature coefficient of maximum energy product for some rare earth

permanent magnets.

Because saturation magnetization is an intrinsic property, it

would be possible to calculate the temperature coefficient of saturation magnetization

for a temperature-compensated R-TM magnet using a simple model, in which it is

assumed that the magnetization of an (LR1-xHRx)-TM

compound is independently contributed by LR-TM and HR-TM. As a first step of the modeling, the

temperature dependence of saturation magnetization of, for example, SmCo5

and GdCo5 alloys should be experimentally determined by obtaining

two functions M1(T) and M2(T). Then, two polynomials can be used to

represent these two functions. Following

that, these two polynomials can be “blended” (added) instead of two actual

alloys, and resulting in a third polynomial.

M3(T)

= (1-x) M1(T) + xM2(T) (7)

where 0 £ x £ 1. Next, the derivative of M3(T)

with respect to T, dM3(T)/dT can be easily determined. Finally, the temperature coefficient of the

new “alloy” at any specific temperature can be derived using

aT =  x 100 [%/ºC]. (8)

x 100 [%/ºC]. (8)

Fig. 26. Temperature dependence of magnetization for

Gd2TM17, Ho2Co17, and Er2Co17.

In other words, the aT vs. T relation for the new “alloy”

can be readily established. Details of

the numerical expression of this approach were given in

[54]. To demonstrate results of this

modeling for temperature-compensated magnets, figures 27 and 28 give the

calculated temperature dependence of magnetization for a few (Sm,Gd)2TM17,

(Sm,Ho)2TM17, (Sm,Er)2TM17,

(Sm,Er,Ho)2TM17, and (Sm,Gd,Er,Ho)2TM17

“magnets”. While Figures 29 and 30 show

plots of calculated temperature coefficients vs. temperature for some of these

“magnets”.

Fig. 27. Calculated

temperature dependence of magnetization for (Sm,Gd)2TM17,

(Sm,Ho)2TM17, and (Sm,Er)2TM17.

Fig. 28. Calculated

temperature dependence of magnetization for (Sm,Gd)2TM17,

(Sm,Gd,Er,Ho)2TM17, and (Sm,Er,Ho)2TM17.

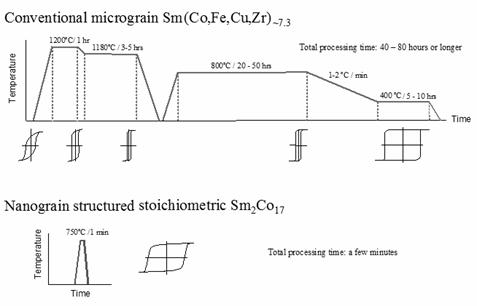

8. Nanograin Structure,

Nanocrystalline and Nanocomposite Sm-Co Magnet Materials

High uniaxial magnetocrystalline

anisotropy is a key prerequisite and a necessary condition for high coercivity

in rare earth magnets; however, it is not the sufficient condition for high

coercivity in conventional rare earth magnets with micrometer grain structure. A convincing example to illustrate this

concept is the Sm2Co17 compound. Though Sm2Co17 has moderately

high uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy of 3.3 MJ/m3, as mentioned previously, the coercivity

of stoichiometric Sm2Co17 is very low (usually less than 200

kA/m), if its grain size is in the micrometer range. In order to develop useful coercivity, extra

Sm and considerable amounts (~10% at%) of Cu and Zr must be added

and a complex and time-consuming heat treatment procedure must be applied

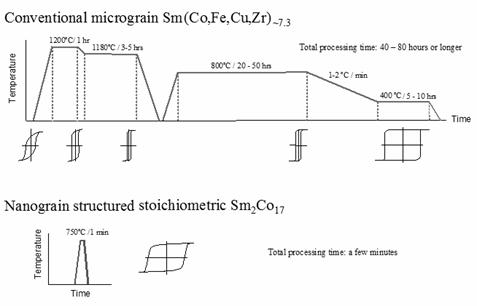

[26-32]. The procedure consists of

high-temperature sintering at ≥ 1200°C for 1 to 3 hours, a solid solution

heat treatment at ~1180°C for 2 - 4 hours, a long-term

isothermal aging at ~800°C for 20 to 50 hours. Even after this long-term isothermal aging,

the coercivity is still very low. As

demonstrated in Figure 31, the high coercivity is developed after a very slow

cooling from 800ºC to 400ºC at 1 - 2ºC/minute followed by another isothermal

aging at 400ºC for 10 - 20 hours. The

whole procedure takes about three days (up to 80 hours) to complete, as shown

in Figure 31. These compositional

modification and long-term heat-treatment are required to form the specific

fine-scale cellular microstructure in which the cell boundary phase serves as

pinning sites for domain wall motion.

However, if the grain size of Sm2Co17

is reduced from micrometer range to nanometer range, high intrinsic coercivity

can be easily developed in the stoichiometric Sm2Co17

(without adding extra Sm and Cu, Zr and without long-term isothermal aging and

slow cooling ). In 1991, J. Wecker [55]

obtained 0.5 MA/m after annealing a mechanically alloyed stoichiometric Sm2Co17

alloy powder at 700°C for 30 minutes. A

few years later, S.K. Chen [56] obtained 0.3 MA/m after annealing a

mechanically alloyed SmCo10 alloy powder at 750°C for 20

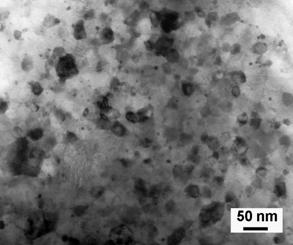

minutes. In 2003, a high coercivity of 1.24

MA/m was accomplished after annealing a high-energy

ball milled stoichiometric Sm2Co17 specimen at 750°C for

only 1 minute as shown in Figure 32 [57].

The TEM observation revealed nanograins of approximately 30 nm in

average and no cellular structure was found as shown in Figure 31. It should be noted that in order to achieve

the similar level of coercivity, its micrograin counterpart must go through a

sintering, a solid solution heat treatment, and a long-term isothermal aging

followed by a very slow cooling, totaling 80

hours, in addition to the Cu and Zr and extra Sm addition. Therefore, magnetization reversal in

nanograin Sm2Co17 must be carried out

by a mechanism other than domain wall pinning.

Fig. 31. Process and coercivity

development comparison of conventional micrograin 2:17 (upper portion) and nanograin 2:17 magnet material (lower portion).

Fig. 32. TEM micrograph of a nanograin Sm2Co17

magnet sample annealed at 750ºC for 1 minute with MHc = 1.24

MA/m.

Apparently, a fundamental change in coercivity

mechanism takes place when the grain size of a rare earth magnet is reduced

from the micrometer range to nanometer range.

Based on novel phenomena observed in magnetic materials having nanograin

structure, a new model of coercivity mechanism in magnetic materials with

nanograins was proposed [58,59]. The

principal points of this model are as follows:

- In

magnetic materials with nanograins, the formation of multiple magnetic

domains in a grain is no longer energetically favorable;

- The

magnetization reversal in nanocrystalline and nanocomposite magnetic

materials is not carried out by nucleation of reversed magnetic domains or

domain wall motion, but by rotation of magnetization;

- Therefore,

in magnetic materials with nanograin structure, there is no longer a need

to create a specific microstructure to prevent the formation of reversed

domains or to restrict domain wall motion;

- High uniaxial

magnetocrystalline anisotropy is not only a necessary condition for high

coercivity, as it is in magnetic materials with micrograins, it is also

the sufficient condition for high coercivity in magnetic materials with

nanograins;

- Thus,

a direct connection between coercivity and magnetocrystalline anisotropy

is established in magnetic materials with nanograin structure;

- Consequently,

high coercivity should be readily obtained for any magnetic materials that

possess high uniaxial anisotropy, provided that the materials have nanograin

structure.

This concept can be schematically

illustrated in Figure 33.

(a) (b)

Fig. 33. Coercivity mechanisms in

rare earth permanent magnets with micrograins (a), showing indirect connection

between anisotropy and coercivity;

and with nanograins (b), showing direct connection between anisotropy and

coercivity.

To verify this concept

experimentally, an YCo5 alloy was chosen for a further test. YCo5 was the first rare

earth-transition metal compound that was discovered to

have very high uniaxial magnetocrystalline anisotropy [4]; however, useful

coercivity could not be obtained in a conventional material with micron

grains. A high-energy ball milled YCo5

powder was annealed at 750°C for 2 minutes, and high coercivity near 1 MA/m was readily obtained in the first experiment [93]. Then, a moderately high coercivity of 0.6

MA/m was obtained after annealing a high-energy ball milled YCo5/a-Fe (5 wt%) at 750°C for 2 minutes [93]. Figure 34 shows a TEM image and selected area

electron diffraction pattern of the nanocomposite YCo5/a-Fe

specimen. The electron diffraction

pattern demonstrates a mixture of a 1:5 structure and an a-Fe

structure, while the TEM image is characterized with small a-Fe

grains and twinned YCo5 grains.

In addition, the new coercivity concept is also supported by

experimental results obtained in Sm2Co17/Co, (Sm,Gd)2Co17/Co, and Nd2Fe14B/a-Fe

systems.

Fig. 34. TEM image and selected area electron

diffraction pattern of a mechanically alloyed YCo5/a-Fe specimen after annealing at 750°C

for 2 minutes [93].

In a nanograin rare earth magnet

material, the rare earth content can be reduced to

lower than its chemical stoichiometric composition, resulting in a hard/soft nanocomposite

magnet material. In nanocomposites,

because of the hard/soft interface exchange coupling, the direction of

magnetization in the soft phase is restricted by that in the hard phase and

tends to be aligned in the same direction as

that in the hard phase. The exchange

interaction of magnetic moments at the hard/soft interface is, in a way, like a spring, leading to the term exchange spring.

Getting rid of excessive Sm content

and eliminating non-ferro-magnetic elements Cu and Zr from the conventional Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets would significantly enhance magnetization and Curie temperature. Stoichiometric Sm2Co17

possesses high saturation magnetization of 1.22 T and high Curie temperature of

917°C. Partial substitute Fe for Co

further increases the saturation magnetization of Sm2(Co0.7Fe0.3)17

to 1.45 T. If nanocomposite Sm2(Co0.7Fe0.3)17/Fe-Co

could be made, its magnetization would reach the same level as Nd2Fe14B

(1.6 T) and it might be a new type of high-temperature and high-performance

magnets, if sufficiently high coercivity could be developed.

However, there are multiple

difficulties to accomplish this task. First,

nanograin structures are created using rapid

solidification, for example melt spinning, and high-energy ball milling

followed by crystallization. The products

of these processes are ribbons or powders.

Making these ribbons and powders fully dense materials without altering

their nanostructure is a challenge. Second,

near perfect grain alignment is necessary for any high-performance magnet

materials. Aligning tiny nanograins,

thus, forming anisotropic magnets is another challenge.

Melt spinning or high-energy ball

milling followed by rapid hot compaction and hot deformation were successfully

employed to make nanocomposite Nd-Fe-B/Fe or Nd-Fe-B/Fe-Co magnets by realizing

fully dense bulk magnets and near perfect grain alignment. The hot compaction is not only a process for

consolidation of powders or ribbons, but also a process for crystallization of

amorphous materials. While in the

followed hot deformation, the hot compacted bulk body is

further made to near full density and the easy magnetization directions

of all nanograins are aligned along the pressing direction [58-59].

However, this approach has proved not

very successful for making Sm2(Co,Fe)17/Fe-Co. Experiments demonstrated that only partial

grain alignment could be established in Sm2(Co,Fe)17 and

Sm2(Co,Fe)17/Fe-Co after hot compaction and hot

deformation [60,61]. This may relate to

the fact that there is no grain boundary Sm-rich phase in the Sm2Co17-based

alloy systems, since it is well known that the grain boundary low-melting-point

Nd-rich phase plays a critical role in grain alignment for Nd-Fe-B alloys

during hot deformation.

Better results were obtained for hot

deformed SmCo5. Bulk, anisotropic, nanograin SmCo5 magnets with

coercivity of 795-3,980 kA/m and (BH)max of 88-135 kJ/m3

were synthesized by hot compacting the high-energy ball milled SmCo5

powder at 700ºC, followed by hot deformation at 800-900ºC with a height

reduction of 70-90% [62]. Figure 35

shows a TEM micrograph of a hot-deformed bulk, anisotropic, nanocrystalline

SmCo5 specimen [62].

Alternatively,

surfactant-assisted high-energy ball milling was used to produce anisotropic

SmCo5 nanoflakes, and the subsequent

magnetic alignment and compaction yielded bulk, anisotropic, nanocrystalline

SmCo5 magnets [63-65]. Figures 36 shows a SEM micrograph of

anisotropic SmCo5 nanoflakes [64].

In addition, many other processes, such as powder blending, powder particle

coating, magnetic field-assisted ball milling, were

tested in recent years.

Fig. 35. TEM

micrograph of hot deformed SmCo5 with 90% height reduction.

Fig. 36. SEM micrograph of anisotropic SmCo5

flakes prepared by surfactant-assisted high-energy ball milling.

It has been nearly 30 years since

Buschow’s group first reported magnetic properties in nanocomposite rare earth

magnet materials [66,67]. However, these

new type of materials, including both Sm-Co and Nd-Fe-B systems, remain in laboratory research stage, and their magnetic

performance is still far poorer than that of their conventional

counterparts. Technical difficulties in

developing practical nanocomposite magnets include not

only how to make bulk, fully dense,

anisotropic magnets using adequate processes, but also how

to develop sufficiently high intrinsic coercivity to ensure linear induction

demagnetization curves.

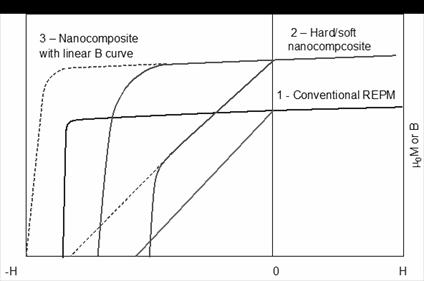

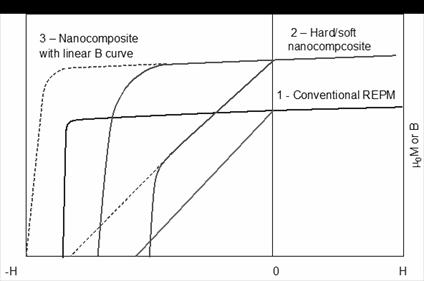

Maintaining a linear induction

demagnetization curve in a hard/soft nanocomposite magnet is a very difficult

task. Introducing a soft magnetic phase,

such as a-Fe or Fe-Co, will certainly enhance the magnetization,

however, it will definitely result in reduced intrinsic coercivity, which will

most likely lead to a non-linear B curve, as illustrated for curve 2 in Figure

37. On the other hand, to remain a

linear B curve, a magnet with higher magnetization needs to have higher

intrinsic coercivity. This would lead to

a contradictory dilemma: making a hard/soft two-phased nanocomposite magnet

that possesses the intrinsic coercivity higher than a magnet without any soft

phase, as shown for curve 3 in Figure 37.

If we consider applications at an elevated temperature, this task would

be even more difficult to accomplish.

It seems a conclusion can be made that only when sufficient high intrinsic coercivity

is successfully developed (in addition to full density and perfect grain

alignment), then nanocomposite magnets would be in a position to compete with

conventional Sm-Co and Nd-Fe-B magnets.

Fig. 37. Schematic illustration showing difficulty in developing

hard/soft nanocomposite with a linear B curve.

9.

Other Sm-Co Permanent Magnet Materials

In

addition to bulk magnets, Sm-Co thin films have been used in areas including,

but not limiting to, microelectromechanical

systems (MEMS) and magnetic recording.

MEMS are miniaturized electromechanical devices, such as motors,

actuators, sensors, mini-pumps, and micro-systems with coupled electric,

mechanical, radiant, thermal, magnetic, and chemical effects. Some MEMS applications require a permanent

magnet film up to a few hundred nanometers in thickness,

while others use a permanent magnet ‘thick

layer’ of a few microns, sometimes even to a few

tenths of millimeters [68].

Permanent

magnets used for MEMS should have (1) proper coercivity, high remanence, high

maximum energy product, and Curie temperature; (2) adequate to MEMS processing;

and (3) environmental stability, including mechanical stability, chemical

stability, and thermal stability. Among

all potential candidates, SmCo5

thin film demonstrates the best magnetic performance;

however, its corrosion resistance is poorer than that of some other

materials, such as Pt-Co [68].

On the other hand, the

perpendicular magnetic recording can provide the storage density three

times more than the traditional longitudinal recording. For the

perpendicular recording, a thin film possessing

high uniaxial anisotropy, with its c-axis perpendicular to the substrate

surface, is required. This can be accomplished by epitaxially growing SmCo5

thin film on an appropriate underlayer [69].

Epitaxial

SmCo5 thin films with strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy have

been developed using sputtering or pulse laser deposition on various

substrates, including Cu, Cu/Ti, W, Cr/Cu, Al2O3 (0001), heated

Ru buffered Al2O3 (0001), Cr

buffered single crystal MgO

(110), and

Ru/Cu/Ru sandwich, etc.

and large perpendicular anisotropy and high coercivity have been achieved [69-72].

10.

Prospects of Future Rare Earth Permanent Magnet Materials

Three generations of rare earth magnets

appeared around the mid-1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, respectively, which made

people believe that we might have a new generation of rare earth magnets in

about every ten years. However, 33 years

have passed since the discovery of Nd-Fe-B magnets, there is still no sign of

any new generation on the horizon. This

fact made some pessimists even think that Nd-Fe-B might be the last

high-performance rare earth permanent magnets.

In order to have reasonable prospects

of future rare earth permanent magnet materials, we have to realize the

distinguished differences between the developments of the 1st, 2nd

generations and the 3rd generation rare earth magnets. It is obvious from Section 2 that the

developments of SmCo5 and Sm2Co17-based

magnets were the outcome of systematic studies of binary R-Co compounds. When research on RCo5 compounds started

from the late 1950s, preliminary versions of R-Co phase diagrams were available

and the existence of RCo5 and some other R-Co compounds were already

known [73]. Researcher’s tasks, then,

became to prepare R-Co intermetallic compounds and to test their basic magnetic

parameters, including saturation magnetization values, Curie temperatures, and

crystalline anisotropy fields, and to determine compounds that have potentials

to be developed into practical permanent magnets.

The development of Nd-Fe-B magnets

was very different from that of SmCo5 and Sm2Co17-based

magnets. To understand this important

deference and its significance, it is necessary to review the discovery of Nd2Fe14B

compound. In fact, searching candidates for

permanent magnet materials was conducted simultaneously in both R-Co and R-Fe

systems. Extensive investigation of R-Fe

systems (R=Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Lu, and Y) was carried out in

the mid-1960s by Ray, Strnat, and their co-workers [74-77] at the US

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and the University of Dayton. Unfortunately, R-Fe binary compounds have

neither high Curie temperature, nor uniaxial crystalline anisotropy, and therefore,

did not appear promising.

In

the 1970s, research on amorphous materials, including soft magnetic materials,

using rapid solidification became very active and stimulated the hope for

finding new metastable phases in R-Fe systems.

In 1973, Clark

[78] obtained an energy product of 69 kJ/m3 by heating a TbFe2

amorphous ribbon to 500°C. Starting from 1980, Croat [79-82] studied

melt-spun R-Fe-alloys (R=Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb, and Er) and obtained (BH)max

= 24-32 kJ/m3 in Nd0.4Fe0.6 and Pr0.4Fe0.6. Apparently, Koon [83,84]

was the first person adding B to melt-spun R-Fe alloys. The purpose of adding B was to restrain the

tendency of the melt-spun alloys to crystallize. Then, Hadjipanayis [85,86] also added Si

and/or B into R-Fe systems to make it easier to obtain amorphous state during

rapid quenching, as he mentioned that “the metalloid was included in the system

to make the ribbons more glassy” [85]. He

also increased the Fe content to enhance the magnetization and obtained (BH)max

= 103 kJ/m3 in Pr16Fe76B5Si3

and Pr16Fe76B8.

The fact that the x-ray diffraction

spectrum of heat treated Pr16Fe76B5Si3

resembled that of a “Fe20R3B” tetragnal phase discovered

by Stadelmaier [87] caused Hadjipanayis to attribute the hard magnetic

properties of R16Fe76(B,Si)8 to this highly

anisotropic phase. Since R3Fe20B

is a stable equilibrium phase, it was realized that the new R-Fe-B magnet might

be made by traditional powder metallurgy method in addition to

melt-spinning. Finally, in November

1983, Sagawa [88] in Japan reported that a (BH)max = 279 kJ/m3

was obtained in Nd15Fe77B8 using the same

conventional powder metallurgy technique as that for producing SmCo5,

which symbolized the birth of the third generation of rare earth permanent

magnets. Later studies revealed that the

exact composition of the new compound is R2Fe14B, not R3Fe20B

as previously realized.

Apparently, the new R2Fe14B

compound was created in early 1980s without even its creator’s (Koon and

Hadjipanayis) recognition. The addition

of B and/or Si into R-Fe was to make it easier to obtain an amorphous phase in

a hope that new metastable phases could be formed in

the heat treatment after rapid solidification.

Therefore, the discovery of Nd2Fe14B is a

fortunate incidental or accidental event, or a “lucky hit,” rather than the

outcome of systematic studies like what happened for SmCo5 and Sm2Co17.

From

the discovery of the Nd2Fe14B compound, there are at

least two lessons we can learn. The

first lesson is that we must pay close attention to every incidental or

accidental event in research. More often

than not, the outcome of a research may be different from the original

intention. This is not only true for Nd2Fe14B,

but also true for the discovery of hard/soft nanocomposite rare earth magnetic

materials.

When Buschow’s

group extended compositions of melt-spun R-Fe-B alloys to a more Fe-rich and

B-rich range, their original intention was, again, to try to find metastable ferromagnetic materials for permanent magnets

[66]. More Fe was added for a higher magnetization

and more B was added for easier glass formation. But, the R2Fe23B3

(R = Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd) metastable ternary Fe-rich compounds they obtained all

have cubic crystal structures and are not suitable for permanent magnet

materials.

Later in 1989, after annealing amorphous melt spun flakes they obtained a two-phased Nd2Fe14B

(15%)/Fe3B (85%) nanocomposite magnet material with remarkable

isotropic hard magnetic properties. The remanence μ0Mr is 1.2 T, intrinsic coercive fields μ0Hc is almost 0.4 T, and (BH)max = 95 kJ/m3 [67]. From that time on started

the extensive research on nanocomposite rare earth permanent magnet materials. Therefore, the discovery of hard/soft

two-phased nanocomposites is very similar to that of Nd2Fe14B

compounds.

It is obvious that Nd2Fe14B

is the first rare earth-transition metal compound with technical importance

discovered in a ternary system. Since

all binary R-Co and R-Fe systems have been thoroughly investigated, the chance

of finding new promising equilibrium or metastable compounds in those systems

is rare. The discovery of Nd2F14B

has opened up a new avenue for future research, which is to explore more

ternary and multiple systems and it expands a vast new field of opportunities. It is reasonable to believe that Nd2Fe14B-based

magnets are not the last high-performance rare earth magnets, but they are the

first high-performance rare earth magnets in a ternary and multiple systems. However, because of the greatly increased complexity

in ternary and multiple systems, it will most likely take quite long time

before the next potential compound to emerge. We should not ignore the possibility that the next

new high-performance magnet material would be discovered

by another fortunate incidental event, like the case of Nd2Fe14B.

The second lesson we can

learn from the discovery of the Nd2Fe14B compound is that

we must pay particular attention to the effect of atomic spacing on intrinsic

magnetic properties. Nd2Fe17

is the only stable compound in the binary Nd-Fe system. It has a rhombohedral crystal structure with

a = 0.857 nm and c = 1.246 nm, unfavorable easy-basal-plane anisotropy, and unfavorable

low Curie temperature of 57°C. By adding B, a new ternary Nd2Fe14B

compound forms. It has a tetragonal

crystal structure with a = 0.879 nm, c = 1.218, uniaxial anisotropy with Ha

= 6 MA/m, and Curie temperature of 312°C. It is believed that

these significant changes are originated from the atomic spacing

variation.

In addition, when nitrogen or carbon was introduced into R2Fe17 as

interstitial atoms, the small increase of lattice constants yielded vast

enhancement in magnetization, Curie temperature, and anisotropy field [89]. For example, comparing Sm2Fe17N3

with Sm2Fe17, only about 2% increase in lattice constants

is demonstrates, but 93% increase in Curie temperature (from 389 K to 749 K),

54% in saturation magnetization (from 1.0 T to 1.54 T), and the anisotropy

changes from easy basal plane to uniaxial with Ha = 11 MA/m.

We simply cannot overemphasize

the significance of atomic spacing, since according to the Bethe-Slater curve, the basic types of

magnetization, such as paramagnetism, ferromagnetism, and antiferromagnetism,

are closely related to atomic spacing.

Altering atomic spacing through forming new compounds may result in a change

of magnetic types. For example, Mn is

antiferromagnetic below 100K and paramagnetic at room temperature. However, Mn shows ferromagnetic in Mn-Al,

Mn-Bi, Cu-Mn-Sn, and Cu-Mn-Al systems.

If in the relatively distant future we are able to modify materials not

only in micrometer and nanometer ranges, but also in an angstrom range by

forming ternary or multiple system compounds, then it might be not impossible

to change a material from paramagnetic or ferrimagnetic to ferromagnetic.

It is assumed that one of the future

high-performance rare earth magnets might still take the form of R-T-M, where R

is one or more rare earths that primarily contribute high crystalline

anisotropy, and R = Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Dy, Ho, or Er; T is one or more 3d (or 4d) transition metals

that primarily contribute high Curie temperature and high magnetization, and T

= Co, Fe, Mn, Cr, or Mo, Nb; and M are one or more metals, or semi-metals, or

non-metal elements, which are primarily to adjust atomic spacing, and M = Al,

Si, Ga, Ge, etc.

Conclusions

In advanced power/propulsion systems

for future aircraft, vehicles, and ships, permanent magnet materials capable of

reliably operating at high temperatures up to ~450°C are required. Those operating temperatures are far beyond

the capability of Nd-Fe-B magnets.

Extensive

research efforts performed around the year 2000 resulted in a new class of Sm2(Co,Fe,Cu,Zr)17-type

magnets capable of operating at high temperatures up to 550°C and these new

magnets are commercially available in the market. However, as a result

of excessive amount of Sm, Cu, and Zr, the

magnetization values of these new magnets are relatively low.

When grain size is

reduced from micrometer to nanometer range, a direct connection between

coercivity and magnetocrystalline anisotropy is established in magnetic

materials. Consequently, high coercivity